In 1547, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V penned a letter to his ambassador, Jean de Saint-Mauris, part of which was written in the ruler's secret code. Nearly five centuries later, researchers have finally cracked that code, revealing Charles V's fear of a secret assassination plot and continued tensions with France, despite having signed a peace treaty with the French king a few years earlier.

The future Holy Roman Emperor was born in 1500 to Philip of Hapsburg and Joanna of Trastamara—daughter of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile in Spain. She was nicknamed "Joanna the Mad" because of her rumored mental illness and actually gave birth to Charles in a bathroom in the wee hours because she insisted on attending a ball despite clearly having labor pains. Generations of inbreeding conferred on Charles an enlarged jaw (mandibular prognathism), a condition that later became known as "Hapsburg jaw," since it became even worse in subsequent generations. Charles also suffered from epilepsy and gout; the latter became so severe late in life that he had to be carried around in a sedan chair.

Charles V began inheriting various family titles at a young age, and his dominion eventually encompassed the Holy Roman Empire—which extended from Germany to northern Italy in the early 16th century and included Austrian hereditary lands, the Burgundian states, and the Kingdom of Spain. During his reign, he continued the Spanish colonization of the Americas and embarked on a short-lived German colonization effort, earning the label "the empire on which the sun never sets." As his health deteriorated, Charles V abdicated as emperor in favor of his brother Ferdinand in 1556, although it was not legally recognized until February 1558. He retired to the Monastery of Yuste in 1557 and died the following September.

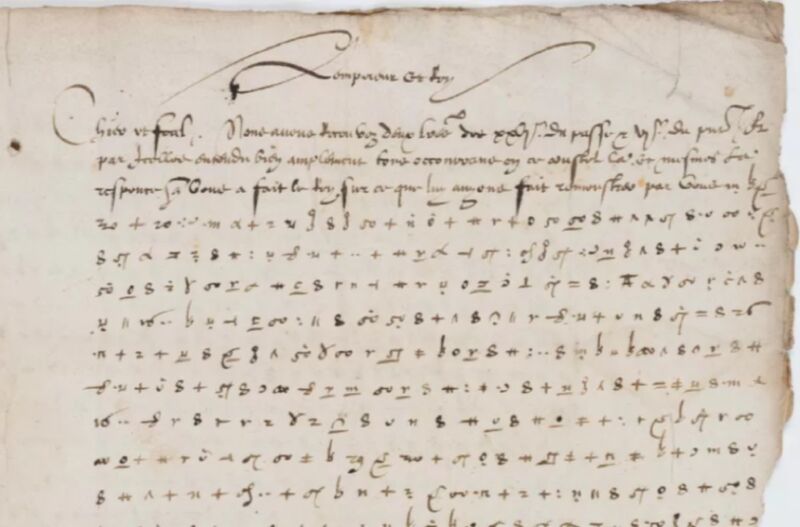

Charles V's three-page letter to his ambassador was written against the backdrop of a fierce struggle against the rising Protestant religion—the emperor was a devout Catholic who denounced Martin Luther as an outlaw at the Diet of Worms in 1521—and continued tensions with Francis I of France. Cecile Pierrot, a cryptographer with the Loria laboratory in France, first heard of the letter's existence at a dinner in 2019 and finally managed to track it down two years later, where it was languishing in the basement of the historic library in Nancy. Pierrot promptly tried to crack the coded portions of that letter by categorizing the various symbols and hunting for telltale patterns.

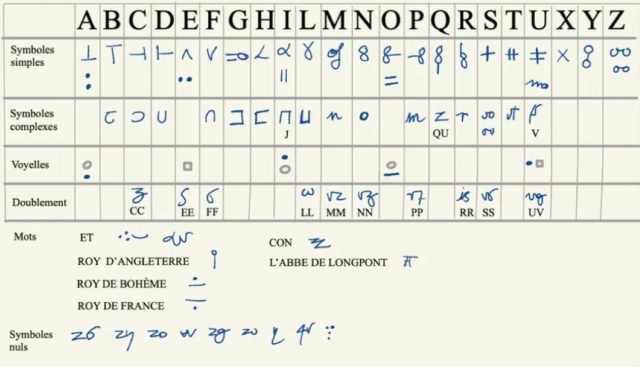

The task proved rather daunting since the approximately 120 encrypted symbols didn't employ a simple symbol-to-letter representation. Granted, most represented letters or combinations of letters, per Pierrot, but others represented entire words—for instance, a needle to represent the English King Henry VIII. Vowels that came after consonants were replaced by diacritical marks, except for the letter 'e' (the most commonly used letter), which the code makers cleverly avoided using as much as possible. And a few symbols didn't seem to serve any function at all. "Simply putting it into a computer and telling the computer to work it out would have literally taken longer than the history of the universe," Pierrot told BBC News.

The big break occurred thanks to historian Camille Desenclos, who directed Pierrot to several other coded letters written by, and sent to, the emperor, one of which turned out to have been informally translated. Pierrot described that letter as their "Rosetta Stone," adding, "It was the key. We would have got there in the end without it, but it saved an awful amount of time." The team hopes to identify and translate other letters between the two men in the coming years.

So what does the letter say? Pierrot and her colleagues have yet to make their full translation public since an academic paper is in the works. But the letter was written in the wake of Henry VIII's death a few weeks earlier and a rebellion in Germany by a Protestant group called the Schmalkaldic League. Per Pierrot, Charles V expressed his wish to keep the peace with France in order to focus his resources on fighting the league, hoping to discourage the French and English from coming to the latter's aid.

Charles V also mentioned a rumor that he was the target of an assassination attempt by an Italian mercenary named Pierre Strozzi, instructing his ambassador to find out as much as possible about the rumor's veracity. (Apparently, it was idle gossip; no assassination plot was uncovered.) Finally, the emperor concocted a strategic response to the news that his nephew, Ferdinand of Tyrol, had been forced to flee a rebellion in Prague. He instructed Saint-Mauris to spread the word that Ferdinand had left Prague by choice to join his father—Charles V's brother—on a campaign.

As for how history played out, Francis I died a few weeks after the letter was written, succeeded by his son, Henri II. Charles V eventually beat back the Schmalkaldic League but failed to stamp out Protestantism in Germany—or in France. Henri II formed an alliance with Protestant princes against the emperor in 1552, and Charles V eventually conceded the Peace of Augsburg (signed by his brother Ferdinand in his name) in 1555.

reader comments

79